A conversation with Meredith Preston McGhie, Secretary General of the Global Centre for Pluralism

By Nazim Karim

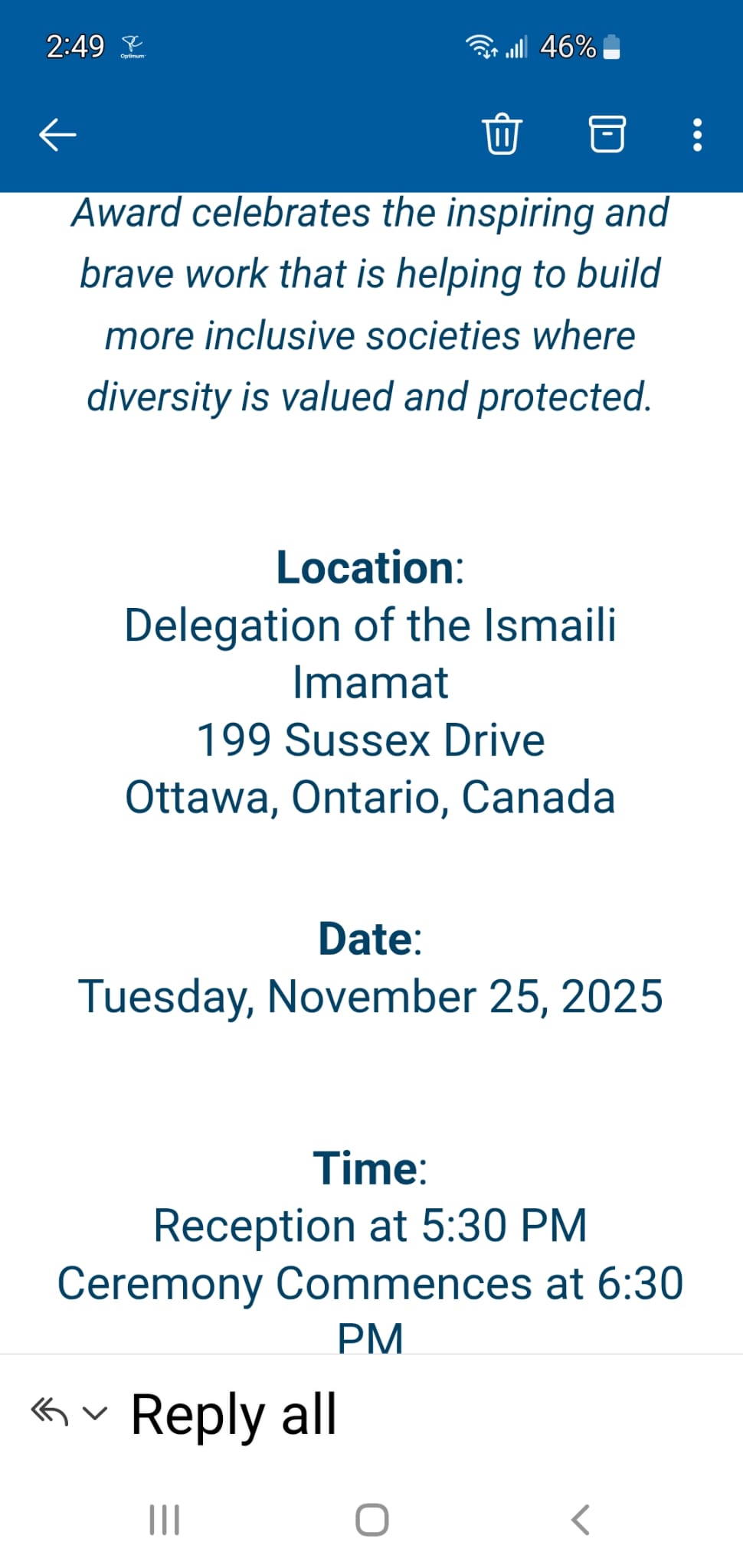

Our interview with Meredith Preston McGhie addresses a range of topics, from the meaning of pluralism to its application in reducing conflicts, changing perceptions of the “other,” and to the work of the Global Centre for Pluralism. The Global Pluralism Award will be conferred this year – the 5th time the prize has been given.

The winners were recently announced, with an award ceremony to take place this November. At a time of growing anxiety, the laureates are phenomenal examples of action toward a better future – building bridges and overcoming division to re-centre positive humanity in some of the world's toughest places. Follow the Global Centre for Pluralism for the latest news on the Award.

Thank you for taking the time to discuss a topic of great urgency in today's world. Perhaps we should begin with an explanation of the distinctions between three related concepts that are used interchangeably but which have different meanings: tolerance, diversity, and pluralism?

These concepts are indeed connected, and we often see confusion so I am happy to start by clarifying it. Diversity is a fact. It exists in all societies. We are diverse ethnically, linguistically, in terms of our faith, our geography, political persuasion, race, gender, and so forth. These diversities exist in different forms in every community, every society around the world.

Pluralism is the set of actions we take to see diversity as a strength to be harnessed to make society better. Each society will have a different path towards pluralism, but the ultimate goal for pluralism is to see diversity as a strength for our collective success. That is the sort of ethic for respect for diversity that His Late Highness so often talked about.

A pluralist society is a long-term aspiration that helps us to frame each decision we take (as governments, institutions, individuals) around how we can all work towards fostering belonging – the dignity and respect of each individual and group in a society.

Therefore, the idea of belonging is equally important to pluralism. It is important to reflect on what it means to belong. To intrinsically feel part of a society, that others see you as part of it, and respect you in your fullest form, and that you can fully participate in the direction of that society.

What is critical about this is that my belonging does not come at the expense of yours, that these things are and must be mutually reinforcing and connected. This is foundational to the development of peaceful, prosperous and just societies and is at the core of pluralism.

Tolerance and social cohesion are important concepts and significant steps on a society’s path to pluralism. When you think about tolerating difference however, you do not think about what I just described – tolerance only gets you part of the way to this more transformative path of pluralism. We embrace approaches to tolerance and use this as an important marker as we talk about other pluralism foundational concepts.

The UN Declaration of Human Rights lists 30 basic rights, such as respect for life, religion, dignity, freedom of expression and so on. But different societies and traditions interpret and prioritize these rights differently. What are Canadian values? Does someone from another country arriving in Canada have to change certain concepts to be able to be Canadian or accepted as fully Canadian? There will always be a retained aspect of cultural tradition and identity, so is there an inevitable conflict here? And how does one resolve that?

There are many ways to try to resolve these tensions – there is not an easy or single answer. One of the questions that I would pose back, if I was in conversation with someone, is to understand what we mean by “values.” Often, when one has a dialogue with different communities about what their values are, there is more in common than many might expect to find. The expression of those values may look different. What concerns me is when statements come from a place of fear rather than a genuine conversation about what our values are and how they connect us.

Too often in our current climate, with social media, we see our identities as fixed and not evolving or adapting. I am also conscious that for some it feels like things are evolving and changing too fast. That is where these reactions often stem from. It is important to find ways of leaning in and having civil discourse around where those values are, in fact, connected.

As an example, we convened a discussion with a Jewish professor of political science in Canada, and a Palestinian law professor in California who work together, trying to understand Israel and Palestine from both of their perspectives, which as you can imagine right now is probably one of the hardest things to do anywhere in the world. I asked them how they do this. And they said, even when they deeply disagree, and even when one has hurt the other in the way that they expressed something, they go back to core shared values. And those values are quite human. Those values are for a peaceful future for the region, for belonging. I do think that when we all go back to those basics, we can find common ground.

Princess Zahra and Ms McGhie congratulate Esther Omam, a peacebuilder from Cameroon and one of three winners of the 2023 Global Pluralism Award.

Photo: Patrick Doyle

While leaders seem to be talking a lot about pluralism, we've seen a continuation of conflicts. There are conflicts in Ukraine, Myanmar, Gaza, Sudan - the list goes on. So, many governments and leaders seem to espouse the notion of pluralism but are not actually practicing it, and the world is not a safer place for many people.

I would like to note that you are talking about political leaders, but it is important that we broaden our notion of leadership. His Late Highness was an example of a leader who expressed a vision that is much deeper and broader. We need to look to a wider range of leaders. We live in a world where conflict is on the rise and many of these have re-emerged because of negligence in addressing core questions of how to engage with diversity. In surveys across Sudan, even in the depths of conflict right now, people point to the failure of building a genuinely inclusive political system as a contributor to the conflict.

So, this failure of pluralist leadership that contributes to these conflicts needs to be addressed. Some politicians I have spoken to remark that their own systems incentivize them to take divisive positions rather than try to draw people into a civil conversation. We increasingly see systems where bases are being mobilized, rather than leaders leaning into the middle ground. We need to come back to engage in what is a large, but often a more silent, middle ground.

That said, much of our work on peace and conflict gives me a sense of optimism in the midst of incredibly difficult, intractable conflicts, because people are talking much more directly about the centrality of pluralism in peace processes than they were 20 years ago. Because they recognize at a deeper level that it is the core failing that they need to address to sustainably resolve conflicts in places like Sudan and Myanmar and elsewhere.

We are seeing increasing divisions within society about all manner of issues, whether it's abortion, the roles of church and state, and, of course, immigration. We are seeing more and more extreme positions and opinions, which political leaders are adopting just to win. Does this present a pessimistic view for the future about the pluralistic vision that we have?

It is indeed a challenge. One of the factors that we have to contend with now is the social media landscape and algorithms prioritize more hardline positions to the top of social media feeds. More work needs to be done to elevate diversity of perspective in these spaces for civil discourse.

For example, one of our phenomenal Global Pluralism Award laureates is a digital peacebuilding organization called “Build Up.” They use digital tools to surface these kinds of conversations in ways that are not polarizing, but to identify consensus around areas where you maybe don't believe that consensus exists.

For example, they often talk about not building consensus, but actually finding consensus through digital tools. So rather than having a social media feed that is divisive and angry, you have a series of polls that draw out people's perspectives, and then the perspectives get adapted and voted on by the online community. As this process happens, those with which people agree start rising to the top.

This surfaces areas of agreement that people didn't realize existed. Sometimes digital space can be helpful in these discussions when people are behind a screen and being well-facilitated, it enables people to talk about something that may be harder to do face-to-face. That is just one example where we see people trying to do things differently.

The challenge is that the social media platforms are behemoths, and they surround us all the time. Often citizens do not know where to seek out these other platforms to have this engagement. We can all be better at figuring out where these platforms are and making sure that they are spread more widely.

Ms McGhie at the Oslo Forum 2022, with Joaquim Alberto Chissano, former President of Mozambique.

Photo: Global Centre for Pluralism

Today, we also have people living in their own ideological bubbles reflecting their notions of a Utopian society. One bubble may be focused on a gun rights, immigration, and a pro-life agenda, and another concerned about the environment, reproductive choice, and so on. So, if people aren't willing to move out of their own dogmatic beliefs and entertain alternative views, how does one broaden their perspectives and have a civil discourse with those whom we disagree, as His Late Highness suggested?

Our silos are certainly a challenge. The recent Edelman Trust Barometer, asked the question: “who do you trust the most to deliver a message to you?” In health messages, scientists still ranked very high. However, almost equally to scientists, the poll showed that people trust “people like myself”. What this finding reminds us of is that we are narrowing our trust to those we believe are like ourselves.

At the same time, I do see people from different “silos” coming together across divides. An initiative that recently gave me hope, is one shepherded by the Carter Center, working across the United States that is cross-partisan, mobilizing to mitigate political violence, where they have Republicans and Democrats coming together. They do not focus on issues on which they disagree but rather on those they do on a shared vision for trust in the electoral process as a baseline in the lead up to the 2024 Presidential elections. This is a reminder that we do have places where we can start to work together.

A lot of the work that we do on leadership training for pluralism around the world starts with core principles of a baseline on which you can build a shared foundation. You do not start with the hardest conversation but rather start with spaces in which you can build trust and confidence. And they exist.

Focusing on the pluralism and tolerance aspects again, we have seen for as long as two decades, an anti-immigrant bias that is now in Europe. We see this as a core question across North America as well. How does the Global Centre address this? Because without immigrants, few countries would manage to have a labor pool. So, how do we change the mindset about immigration as positive for society?

Some previous research in Canada is interesting in this respect. In one study, people were asked how “Canadian” they feel, and then were asked how they feel about migrants in their society. In most societies if one expresses greater patriotism, one tends to express less support for immigration. In Canada, this opposite was found to be true. There has been a long-standing recognition of the value and importance of immigration to building what Canada is today. That is an important thing to remember, given the tensions over these last couple of years, but I want to remind us of that baseline because it is important to preserve this element of our Canadian identity.

What we see in terms of successes that may have led to this sentiment in the past is when we have a clear plan on how to engage with immigration, to ensure that the incredible skills that newcomers bring to Canada are utilized. How we accredit newcomers, how we support leaders who will be helping to engage new Canadians in their communities and institutions is central to the success – for everyone.

We are very excited that we are beginning some work on pluralism leadership training in Canada to support newcomer teachers which we hope will also serve to contribute to improving school environments for all children.

The private sponsorship of refugees in Canada is another community-based example of communities opening their doors and their hearts, quite literally, to incoming refugees. Because the community is responsible for how that family settles in Canada, you see a much greater degree of success of how those families have been able to set themselves up. UNHCR uses this as a global example because it is belonging-centered. That is what we are seeking to do on the education front and I know it can be replicated in other areas.

Education is key to changing attitudes, so what is the Centre doing in terms of curriculum? Training teachers in one aspect but is there something for students that has been inserted into curriculum that promotes a pluralist mindset?

We focus on the role of educators, the role of school administrators, and the entire environment of schools. While curriculum development is important, developing content for national-level curricula around the world is a massively time-intensive and heavy lift.

We identify core program pillars for GCP where we can have outsized impact. One of those focuses on leadership in education and leadership for pluralism. Ensuring that teachers and school administrators and heads of teachers’ unions and school boards have the tools to be able to engage with difficult topics, and to support learning that centres belonging, and pluralism throughout.

For example, one of our Global Pluralism Award winners from 2019, “Learning History That Is Not Yet History,” was a collective of history educators in the Balkans that got together and said, we need different tools to teach our national histories. These are history educators from different countries in the Balkans recognizing that the curricula that they had was setting them up for division and potentially for conflict in the future.

They recognized that because often history curriculum is a political act in societies, it is not easy to change, however the teachers could change how they were teaching it so that students were seeing the multiple perspectives in past conflicts as well as understanding the diversity in society today.

Secretary General McGhie in conversation with Ms Gillian Triggs, Assistant High Commissioner for Protection at the United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

Photo: Global Centre for Pluralism

The U.S. World History curriculum devotes around three per cent of its content to discussions of Muslims and Arabs, glossing over their contributions to science and philosophy. But where is content on the Malian Empire, the cycles of history of Ibn Khaldun, or knowledge about Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine, and so many others? If we’re going to have a truly pluralistic society, would a more comprehensive approach not encourage a better understanding of peoples, their cultures, and contributions?

Absolutely, more comprehensive history education is critical. History education is how we tell our children what has come before them and how to imagine their citizenship and their society. Therefore, what we do not tell them and how we tell it is as important as what we do tell in our history education.

When I was working in East Africa and was the advisor to His Excellency Kofi Annan following the post-election violence in Kenya in 2008, one of the issues that was raised was the need to reimagine the history curriculum for education in Kenya to tell the story of many communities that had suffered throughout the country’s history. This was such a sensitive discussion – it is a demonstration of how much it is at the heart of how we understand our identities.

As a Pluralism Centre with emphasis on “global,” what would you say have been the major projects of the Centre and its successes?

We are a global institution with deep roots in Canada rather than a Canadian institution exporting Canadian ideas. Pluralism is a universal idea and therefore it is important that we learn and engage globally. I am particularly pleased with the recent launch of the Global Pluralism Monitor, a comprehensive tool to understand the state of pluralism in countries around the world.

We work with a global network of practitioners in their countries to understand how pluralism expresses itself in the institutions, laws and policies, in the norms and narratives, and in leadership in those societies. The Monitor is an action-oriented tool, designed to be a resource for leaders to take forward a different set of conversations to engage peacefully and productively with their diversity. That is very much the core of how we operate, that each place we go, we try to understand the context. We meet the society where it is at, we take direction from our partners, and we build out a program of work.

It has been gratifying to see the uptake of this in different countries. In Colombia, for example, we were requested by Indigenous and Afro-Colombian women leaders to work with them to adapt the Monitor framework and to build a new way for communities to engage with the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. This has been particularly important for us because this agreement contains some of the most pluralist elements of any peace agreement. However, it still has a long way to go in its implementation. Bringing a new resource to these efforts in partnership with leaders in Colombia is an honour.

In Ghana, when we launched the Monitor report, it was utilized by our partners as part of a national campaign to re-energize legislation called the “Affirmative Action Bill” in Parliament, that focuses on equality of women and girls but which had been languishing for about a decade. Their campaign culminated in the adoption of the Bill, which we are thrilled to see. So, the Monitor gives us these opportunities to engage deeply with partners around the world.

I would also just point to some of our work in Sudan where we have had the opportunity to advise a diverse collection of Sudanese civilian leaders to end the war in Sudan which culminated earlier this year in a large and diverse founding conference in Addis Ababa. We were thrilled to play a small part around the diversity of that group, and constructive engagement with differences gives hope, even in the middle of the conflict.

We engage deeply on issues of leadership across our programs. We focus on questions of how young leaders in education, in peacemaking, engage as pluralist leaders at a time when there is so much polarization and division. The Global Pluralism Award is an important effort to bring these pluralist leaders to global attention and has been a flagship from the inception of the Centre.

Have the Awards themselves made a bigger impact in their own countries and on their work?

Often the best way to inspire action towards pluralism is to demonstrate it in practice. This is what the Awardees are able to do –from building peace to educating, to social enterprises, the arts and other sectors.

The Award provides visibility and gives opportunities for our laureates to deepen their work. We co-create with the Awardees to be as responsive as possible to the needs that they identify. Esther Omam, one of our 2023 winners, is doing phenomenal work at the grassroots around peace in Cameroon at a very difficult and sensitive time.

Bringing the Awardees together to share strategies, advice, and support with one another has also been really valuable – to create a pluralist leaders’ network of support.

The impacts are wide-ranging, I would say, and I think not only within their societies themselves, but also their ability to replicate this work or inspire the replication of their work in other places. They are inspiring examples for us and others, we see important partnerships develop out of the Award.

Meredith McGhie with Women Heads of Diplomatic Missions in Ottawa, at the Global Centre for Pluralism.

Photo: Global Centre for Pluralism

The Centre is teaching people about pluralism, encouraging them to act on those values, and to improve societies in that way. Might it be useful for the GCP to have satellite campuses in certain countries where it trains people in the concept of pluralism so that they can then use their skills in their own societies, talk with the media, youth, different groups, as opposed to intervening on a case-by-case basis?

While I agree with you that we are teaching and providing tools and advice, this is not teaching in a classroom setting – and we are learning as well. We identify partners around the world that are already working on pluralism in different ways – they are experts in these issues in their societies. We bring a holistic frame, a range of comparative experiences and tools, but partners and leaders are already doing this work in their own spaces. We are therefore co-creating with them based on the needs, possibilities and opportunities in that context. It is therefore not about offices or campuses, but rather engagement and relationships to support their leadership.

Each society has its own path. How Ghanaians talk about pluralism will be different from how Colombians, or Kenyans or Sudanese talk about pluralism. There is power in these conversations happening by Ghanaians in a Ghanaian context and a Ghanaian way, or Colombian and so on. Our role is to help boost those spaces.

You will see our fingerprints on a lot of these spaces, but we are not flying a GCP “flag.” This can be counterproductive. Many of these discussions are hard to have and need to be led by figures in that society who are trusted and can work through the nuances. And we will work with those leaders, but we do not necessarily see ourselves being out front in these spaces.

His Late Highness mentioned human rights as being important for democracy. But today, we are seeing human rights being violated in many places. Is there a way to resolve this dilemma or assert that human rights are universal and that certain actions need to be taken to respect this on a consistent basis when such rights are violated?

I think the first thing to say is you are absolutely right, to say that human rights are universal and then watching what's happening globally the statement rings hollow and that is a massive global challenge.

The advancement of human rights is a core goal, and human rights are intrinsic within a pluralist society. Our approach advancing pluralism enables us to come at the conversation differently. These are linked, and mutually reinforcing. However, it is important to have the pluralist conversation as a space to have a different kind of dialogue.

What pluralism offers is a way of having a real conversation that is rooted in values of embracing diversity, and as such gets us to a space where human rights can be reinforced.

A pluralist society is one in which human rights will be recognized and respected. But rather than starting with the rights-based conversation, we are starting with a conversation around how to embrace diversity and work towards a shared sense of belonging, understanding the inherent challenges to do so. We focus on those areas that can unite, rather than those that divide. This enables a series of openings that would not necessarily be open to a conversation otherwise. I think it is important that we focus real effort and resources on creating and convening these spaces.

This has been very educational and informative. Thank you for your time, and for your remarkable work with the Centre.

https://the.ismaili/us/en/news/a-conver ... -pluralism