The Aga Khans during the 19th- 20th Century - Documents

The Aga Khans during the 19th- 20th Century - Documents

This section has been created to share and discuss the migration of Aga Hassanali Shah from Persia to India and the relation of the first Aga Khan, Mowlana Aga Ali Shah up To Mowlana Sultan Muhammad Shah and the present Imam with the British from a historical perspective but also with other countries.

Last edited by Admin on Sun Feb 12, 2017 4:04 am, edited 6 times in total.

This thesis is available on the net:

EXALTED ORDER: MUSLIM PRINCES AND THE BRITISH EMPIRE

1874-1906

KRISTOPHER RADFORD

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN

PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN HISTORY

YORK UNIVERSITY

TORONTO, ONTARIO

OCTOBER 2013

© KRISTOPHER RADFORD, 2013

here is an extract of interest to us:

Outside of Great Britain, where bishops of the Church of England sat in the House of

Lords, it was unusual for religious figures to be so completely integrated into political

structures by the British, the sole other example was the Aga Khan. In 1906, the year

Muhammadu Attahiru II was made a CMG, His Highness Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah,

Aga Khan III was made a GCIE by the Government of India who to all intents and

purposes treated him like an Indian prince.157 However, unlike an Indian prince he ruled

over no territory, but was instead the hereditary Imam of the world’s Ismaili Muslims,

and great number of whom, including the Aga Khan himself, lived in India. The place of

the Aga Khan was anomalous in India just like the place of the Sultan of Sokoto was in

Nigeria. The British, however, when faced with the challenge of integrating the heads of

important religious communities did not conceptualise them in a novel or unique fashion,

but rather sought to integrate them into an existing model of indirect rule as if they were

analogous to hereditary temporal rulers.158

EXALTED ORDER: MUSLIM PRINCES AND THE BRITISH EMPIRE

1874-1906

KRISTOPHER RADFORD

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN

PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN HISTORY

YORK UNIVERSITY

TORONTO, ONTARIO

OCTOBER 2013

© KRISTOPHER RADFORD, 2013

here is an extract of interest to us:

Outside of Great Britain, where bishops of the Church of England sat in the House of

Lords, it was unusual for religious figures to be so completely integrated into political

structures by the British, the sole other example was the Aga Khan. In 1906, the year

Muhammadu Attahiru II was made a CMG, His Highness Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah,

Aga Khan III was made a GCIE by the Government of India who to all intents and

purposes treated him like an Indian prince.157 However, unlike an Indian prince he ruled

over no territory, but was instead the hereditary Imam of the world’s Ismaili Muslims,

and great number of whom, including the Aga Khan himself, lived in India. The place of

the Aga Khan was anomalous in India just like the place of the Sultan of Sokoto was in

Nigeria. The British, however, when faced with the challenge of integrating the heads of

important religious communities did not conceptualise them in a novel or unique fashion,

but rather sought to integrate them into an existing model of indirect rule as if they were

analogous to hereditary temporal rulers.158

http://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/n ... chill.html

The wisdom of Aga Khan and his friend Churchill

Saturday, 11 February 2017

Hassan Al Mustafa

“One of the facts that I learned in life is that the importance of the bargain lies in providing a passageway for difficult times, where you could use this passageway later on to implement comprehensive reforms that would have been impossible without the bargain in the first place.”

The “Political bargaining” between opponents and reaching common ground solutions, which was mentioned by Sultan Mohammed Shah Husseini, in his book “The Memoirs of Aga Khan”, is one of the features of this leader, who carried out very sensitive missions during and after the critical era of the British rule of India and the World war I in 1914.

Aga Khan III had a realistic vision towards the occurring events because he was responsible of leading several millions of Muslims distributed in a number of countries in the world, speaking different languages, and having diverse traditions and cultures. Aga Khan did not count on “violence”; he was well aware of his potentials as well as the weaknesses of others. We cannot disregard the historical side of this matter, especially that he spoke about his love for reading in his memoirs, which gave him a vision from the experiences of his predecessors; he turned these experiences into a practical approach. He said: “I admit that I have worked all my life according to the principle that settlement is better than the intransigent dispute that does not lead us to anywhere.”

Aga Khan was not a weak leader and Churchill did not lack of strength, but rather the wisdom that politics needs to be comprehensive

Hassan Al Mustafa

This “flexible mentality” of Aga Khan III allowed him to play important roles. In 1905, King Georges V sent him more than one message “urging and encouraging him to carry on his efforts to find a solution to the differences between Hindus and Muslims, and thus they would be able to focus on scientific, economic and social reforms.”

Sultan Mohammed Shah, had friendship ties for more than half a century with Sir Winston Churchill. The “political realism” marked both men. Sultan Aga Khan wrote: “every time I discussed political issues with Sir Winston, I got influenced over and over again with the practical realism, which is characterized in his point of views. He is not locked in his previous ideas, wishes or dreams as he controls all of them.”

In this regard, Churchill has once said to his friend that “half a loaf is better than nothing,” when Sir Churchill accepted the fact “that India shall remain within the Commonwealth as a republic that has its own terms.”

Aga Khan was not a weak leader and Churchill did not lack of strength, but rather the wisdom that politics needs to be comprehensive.

This article was first published in Al Riyadh.

___________________

Hassan AlMustafa is Saudi journalist with interest in middle east and Gulf politics. His writing focuses on social media, Arab youth affairs and Middle Eastern societal matters.

Last Update: Saturday, 11 February 2017 KSA 10:26 - GMT 07:26

The wisdom of Aga Khan and his friend Churchill

Saturday, 11 February 2017

Hassan Al Mustafa

“One of the facts that I learned in life is that the importance of the bargain lies in providing a passageway for difficult times, where you could use this passageway later on to implement comprehensive reforms that would have been impossible without the bargain in the first place.”

The “Political bargaining” between opponents and reaching common ground solutions, which was mentioned by Sultan Mohammed Shah Husseini, in his book “The Memoirs of Aga Khan”, is one of the features of this leader, who carried out very sensitive missions during and after the critical era of the British rule of India and the World war I in 1914.

Aga Khan III had a realistic vision towards the occurring events because he was responsible of leading several millions of Muslims distributed in a number of countries in the world, speaking different languages, and having diverse traditions and cultures. Aga Khan did not count on “violence”; he was well aware of his potentials as well as the weaknesses of others. We cannot disregard the historical side of this matter, especially that he spoke about his love for reading in his memoirs, which gave him a vision from the experiences of his predecessors; he turned these experiences into a practical approach. He said: “I admit that I have worked all my life according to the principle that settlement is better than the intransigent dispute that does not lead us to anywhere.”

Aga Khan was not a weak leader and Churchill did not lack of strength, but rather the wisdom that politics needs to be comprehensive

Hassan Al Mustafa

This “flexible mentality” of Aga Khan III allowed him to play important roles. In 1905, King Georges V sent him more than one message “urging and encouraging him to carry on his efforts to find a solution to the differences between Hindus and Muslims, and thus they would be able to focus on scientific, economic and social reforms.”

Sultan Mohammed Shah, had friendship ties for more than half a century with Sir Winston Churchill. The “political realism” marked both men. Sultan Aga Khan wrote: “every time I discussed political issues with Sir Winston, I got influenced over and over again with the practical realism, which is characterized in his point of views. He is not locked in his previous ideas, wishes or dreams as he controls all of them.”

In this regard, Churchill has once said to his friend that “half a loaf is better than nothing,” when Sir Churchill accepted the fact “that India shall remain within the Commonwealth as a republic that has its own terms.”

Aga Khan was not a weak leader and Churchill did not lack of strength, but rather the wisdom that politics needs to be comprehensive.

This article was first published in Al Riyadh.

___________________

Hassan AlMustafa is Saudi journalist with interest in middle east and Gulf politics. His writing focuses on social media, Arab youth affairs and Middle Eastern societal matters.

Last Update: Saturday, 11 February 2017 KSA 10:26 - GMT 07:26

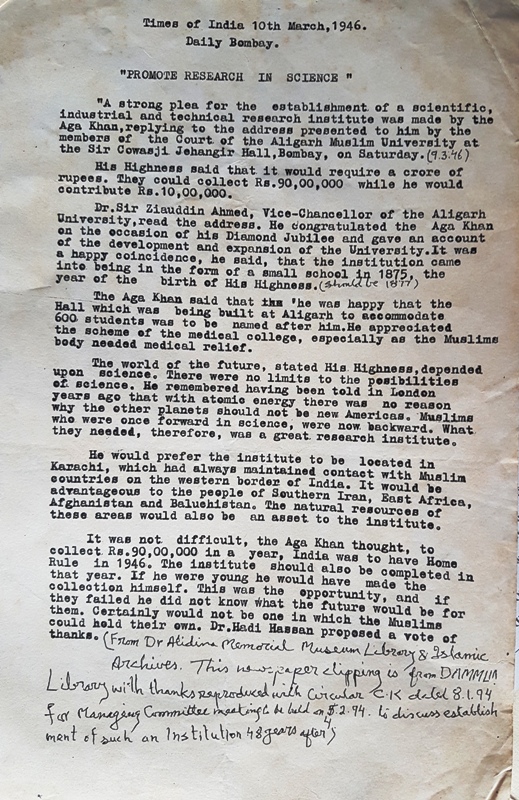

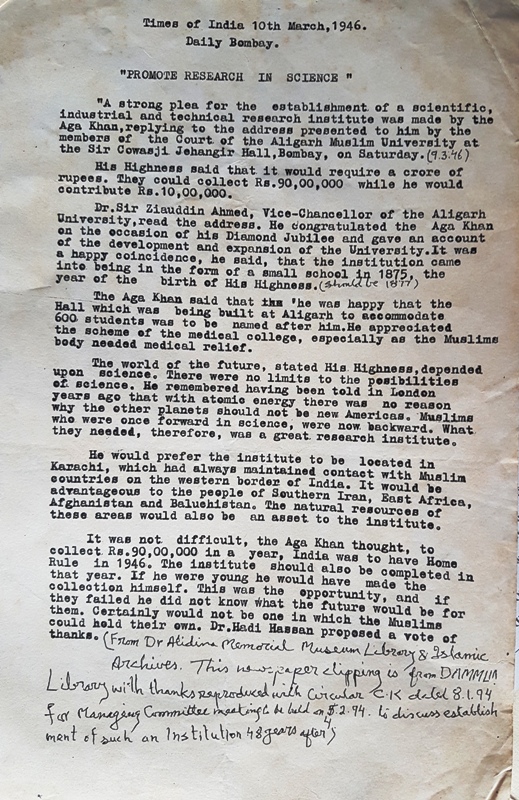

Aga Khan III - Times of India 1946-03-10

Mowlana Sultan Muhammad Shah's interest in education and particularly science and technology for the sub-continent in 1946:

Received from Vazir Sherali Alidina in 1994.

Received from Vazir Sherali Alidina in 1994.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I began the modern phase in the history of the Nizari Ismailis

Imam Hasan Ali Shah was born in Kahak in 1804 and succeeded to the Imamat at the age of 13, after his father was murdered in Yazd, Persia. His mother Bibi Sarkara (d. 1851) went to the court of the ruling Qajar monarch Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) to seek justice for the murder of her husband and support for her family. Fath Ali Shah eventually punished the perpetrators of the crime and compensated the family by granting Hasan Ali Shah additional lands in Mahallat, which had been the family’s residence for some time.

Imam became involved in the public life of his native province. In time, Fath Ali Shah appointed him governor of the district of Qumm and bestowed upon him the honorific title of Aga Khan (Aga Khan) – a title that has remained in use by his successors to the present Imam.

By the time of Fath Ali Shah’s death, Imam had established a military force and a strong presence among the Persian nobility. In 1835, Muhammad Shah (r. 1834-1848), Fath Ali Shah’s grandson and successor, appointed Imam governor of the province of Kirman. At the time, there was much political unrest in the province and Imam brought calm to the region. However, despite his successes, he was informed that he would be replaced by one of the monarch’s brothers. Imam refused to accept his dismissal and was confined to the citadel of Bam along with his family and his army; he surrendered after 14 months when the accusations against him in the civil unrest were proven false. Imam was taken to Kirman in captivity, eventually being permitted to return to Mahallat.

Owing to further political unrest, Imam migrated to Qandahar, Afghanistan in 1841, marking the end of the Persian period in Nizari Ismaili history that had lasted some seven centuries since Alamut time.

In Afghanistan, Imam Hasan Ali Shah associated with the British offering his services to them. He subsequently migrated to Sind in the Indian subcontinent where he resided in Jerruck (now in Pakistan), continuing to offer his services to the British. In 1844, Imam travelled to Karachi, Cutch, Kathiavar, and Calcutta, eventually settling permanently in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1848. This began the modern phase in the history of the Nizari Ismailis, and an era of regular contact between Imam and the widely dispersed communities. Imam continued to maintain a close relationship with the British who came to addressed him as His Highness.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah continued the communal organisation established by Pir Sadr al-Din in the 15th century. Pir Sadr al-Din converted large numbers of Hindus giving them the Persian title khwaja, meaning lord or master, corresponding to the term thakur by which the Hindus were addressed. Pir Sadr al-Din is credited with establishing the first jamatkhana in the fifteenth century in Kotri, Sind, with additional ones in Panjab and Kashmir, and subsequently extending the da’wa to the State of Gujarat.

While many Khoja Ismailis in the subcontinent acknowledged Imam Hasan Ali Shah as their spiritual leader, several others challenged the authority he claimed, taking their grievances to court. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were several communities in the subcontinent who had developed in isolation from the Imamate due to the need for the Imams to practice concealment (taqiyya) for centuries, in order to escape persecution. A number of communities in the subcontinent traced their allegiance to Nizari Ismaili pirs and had developed their own models of governance and forms of leadership. In addition, the British had established direct rule over most of the subcontinent seeking to govern a heterogeneous region by classifying the people based on religion. To clarify the situation for the Khoja Ismailis, Imam Hasan Ali Shah circulated a document in 1861, in Bombay and elsewhere, stating the Khojas were Shi’i Ismailis, and included the beliefs, customs, and practices, and his role as the leader of the community. Those who accepted the terms in the document were asked to sign it. A minority group challenged the terms and filed a lawsuit.

The case, referred to as the Aga Khan Case, was tried by Sir Joseph Arnould in 1866 at the Bombay High Court. The judgement “legally established the status of the community, referred to as ‘Shia Imami Ismailis’ and of the Imam as the murshid or spiritual head of that community and heir in lineal descent to the imams of Alamut” (Daftary, The Isma’ilis Their history and doctrines p 56). The ruling also legally endorsed the Khojas as a single united group of the Raj, whose leader’s role was to govern their affairs and define their religious practices. The ruling was profound, considering that only a few decades earlier, Imams and members of the community were living in concealment.

During the three decades of his residence in the subcontinent, Imam Hasan Ali Shah organised the community through a network of officers called mukhi and kamadia for jamats of a certain size. He also attended the jamatkhana in Bombay on special occasions and led the public prayers of the Khojas. Every Saturday, when in Bombay, he held darbar, giving audience to the jamat.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I died in 1881 after an eventful Imamat of 64 years, and was buried at Hasanabad in the Mazagaon area of Bombay. He was succeeded by his son Aqa Ali Shah Aga Khan II.

Aga Khan Hasanabad Bombay Mumbai

Imam Hasan Ali Shah’s mausoleum in Mumbai. Source: Raiba Anjali Dileep, The Unknown Mumbai

Sources:

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, The Isma’ilis, Their history and doctrines, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/06/30/imam-hasan-ali-shah-aga-khan-i-began-the-modern-phase-in-the-history-of-the-nizari-ismailis/?utm_source=Direct

Imam Hasan Ali Shah was born in Kahak in 1804 and succeeded to the Imamat at the age of 13, after his father was murdered in Yazd, Persia. His mother Bibi Sarkara (d. 1851) went to the court of the ruling Qajar monarch Fath Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) to seek justice for the murder of her husband and support for her family. Fath Ali Shah eventually punished the perpetrators of the crime and compensated the family by granting Hasan Ali Shah additional lands in Mahallat, which had been the family’s residence for some time.

Imam became involved in the public life of his native province. In time, Fath Ali Shah appointed him governor of the district of Qumm and bestowed upon him the honorific title of Aga Khan (Aga Khan) – a title that has remained in use by his successors to the present Imam.

By the time of Fath Ali Shah’s death, Imam had established a military force and a strong presence among the Persian nobility. In 1835, Muhammad Shah (r. 1834-1848), Fath Ali Shah’s grandson and successor, appointed Imam governor of the province of Kirman. At the time, there was much political unrest in the province and Imam brought calm to the region. However, despite his successes, he was informed that he would be replaced by one of the monarch’s brothers. Imam refused to accept his dismissal and was confined to the citadel of Bam along with his family and his army; he surrendered after 14 months when the accusations against him in the civil unrest were proven false. Imam was taken to Kirman in captivity, eventually being permitted to return to Mahallat.

Owing to further political unrest, Imam migrated to Qandahar, Afghanistan in 1841, marking the end of the Persian period in Nizari Ismaili history that had lasted some seven centuries since Alamut time.

In Afghanistan, Imam Hasan Ali Shah associated with the British offering his services to them. He subsequently migrated to Sind in the Indian subcontinent where he resided in Jerruck (now in Pakistan), continuing to offer his services to the British. In 1844, Imam travelled to Karachi, Cutch, Kathiavar, and Calcutta, eventually settling permanently in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1848. This began the modern phase in the history of the Nizari Ismailis, and an era of regular contact between Imam and the widely dispersed communities. Imam continued to maintain a close relationship with the British who came to addressed him as His Highness.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah continued the communal organisation established by Pir Sadr al-Din in the 15th century. Pir Sadr al-Din converted large numbers of Hindus giving them the Persian title khwaja, meaning lord or master, corresponding to the term thakur by which the Hindus were addressed. Pir Sadr al-Din is credited with establishing the first jamatkhana in the fifteenth century in Kotri, Sind, with additional ones in Panjab and Kashmir, and subsequently extending the da’wa to the State of Gujarat.

While many Khoja Ismailis in the subcontinent acknowledged Imam Hasan Ali Shah as their spiritual leader, several others challenged the authority he claimed, taking their grievances to court. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were several communities in the subcontinent who had developed in isolation from the Imamate due to the need for the Imams to practice concealment (taqiyya) for centuries, in order to escape persecution. A number of communities in the subcontinent traced their allegiance to Nizari Ismaili pirs and had developed their own models of governance and forms of leadership. In addition, the British had established direct rule over most of the subcontinent seeking to govern a heterogeneous region by classifying the people based on religion. To clarify the situation for the Khoja Ismailis, Imam Hasan Ali Shah circulated a document in 1861, in Bombay and elsewhere, stating the Khojas were Shi’i Ismailis, and included the beliefs, customs, and practices, and his role as the leader of the community. Those who accepted the terms in the document were asked to sign it. A minority group challenged the terms and filed a lawsuit.

The case, referred to as the Aga Khan Case, was tried by Sir Joseph Arnould in 1866 at the Bombay High Court. The judgement “legally established the status of the community, referred to as ‘Shia Imami Ismailis’ and of the Imam as the murshid or spiritual head of that community and heir in lineal descent to the imams of Alamut” (Daftary, The Isma’ilis Their history and doctrines p 56). The ruling also legally endorsed the Khojas as a single united group of the Raj, whose leader’s role was to govern their affairs and define their religious practices. The ruling was profound, considering that only a few decades earlier, Imams and members of the community were living in concealment.

During the three decades of his residence in the subcontinent, Imam Hasan Ali Shah organised the community through a network of officers called mukhi and kamadia for jamats of a certain size. He also attended the jamatkhana in Bombay on special occasions and led the public prayers of the Khojas. Every Saturday, when in Bombay, he held darbar, giving audience to the jamat.

Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I died in 1881 after an eventful Imamat of 64 years, and was buried at Hasanabad in the Mazagaon area of Bombay. He was succeeded by his son Aqa Ali Shah Aga Khan II.

Aga Khan Hasanabad Bombay Mumbai

Imam Hasan Ali Shah’s mausoleum in Mumbai. Source: Raiba Anjali Dileep, The Unknown Mumbai

Sources:

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, The Isma’ilis, Their history and doctrines, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/06/30/imam-hasan-ali-shah-aga-khan-i-began-the-modern-phase-in-the-history-of-the-nizari-ismailis/?utm_source=Direct

https://www.dawn.com/news/1573083

From The Past Pages Of Dawn: 1945: Seventy-five years ago: Aga Khan’s view

Dawn Delhi 07 Aug 2020

LOURENCO MARQUES: The fear that establishment of an Indian Central Government might be impracticable was expressed by the Aga Khan on his arrival at Lourenco Marques en route to the South African Union.

“It must be remembered that the territories of British India were brought together by British conquest within the last 150 years, and there are wide historical language and racial differences,” he said. “It will be easy to unite them as a Commonwealth but, on the other hand, I have great fear that a Central Government for them may not be practical politics.”

Asked if he thought that world peace would be maintained, the Aga Khan said that if it is possible to bring about in Europe, Asia and later Africa, confederation of vast economic units with equal facilities for movement of population, goods and wealth such as existed in the United States of America, he believed, a permanent world peace was possible. If [not], sooner or later, difficulties in obtaining the necessities for bare living would lead to friction, enmity and hostilities. The Aga Khan thanked the Portuguese Government and people for kindness always shown to the Indians especially his own followers, the Ismailis.

Published in Dawn, August 7th, 2020

From The Past Pages Of Dawn: 1945: Seventy-five years ago: Aga Khan’s view

Dawn Delhi 07 Aug 2020

LOURENCO MARQUES: The fear that establishment of an Indian Central Government might be impracticable was expressed by the Aga Khan on his arrival at Lourenco Marques en route to the South African Union.

“It must be remembered that the territories of British India were brought together by British conquest within the last 150 years, and there are wide historical language and racial differences,” he said. “It will be easy to unite them as a Commonwealth but, on the other hand, I have great fear that a Central Government for them may not be practical politics.”

Asked if he thought that world peace would be maintained, the Aga Khan said that if it is possible to bring about in Europe, Asia and later Africa, confederation of vast economic units with equal facilities for movement of population, goods and wealth such as existed in the United States of America, he believed, a permanent world peace was possible. If [not], sooner or later, difficulties in obtaining the necessities for bare living would lead to friction, enmity and hostilities. The Aga Khan thanked the Portuguese Government and people for kindness always shown to the Indians especially his own followers, the Ismailis.

Published in Dawn, August 7th, 2020